When India became independent in August 1947, it faced a series of very great challenges. As a result of Partition, 8 million refugees had come into the country from what was now Pakistan. These people had to be found homes and jobs. Then there was the problem of the princely states, almost 500 of them, each ruled by a maharaja or a nawab, each of whom had to be persuaded to join the new nation. The problems of the refugees and of the princely states had to be addressed immediately. In the longer term, the new nation had to adopt a political system that would best serve the hopes and expectations of its population.

When India became independent in August 1947, it faced a series of very great challenges. As a result of Partition, 8 million refugees had come into the country from what was now Pakistan. These people had to be found homes and jobs. Then there was the problem of the princely states, almost 500 of them, each ruled by a maharaja or a nawab, each of whom had to be persuaded to join the new nation. The problems of the refugees and of the princely states had to be addressed immediately. In the longer term, the new nation had to adopt a political system that would best serve the hopes and expectations of its population.

India’s population in 1947 was large, almost 345 million. It was also divided. The citizens of this vast land spoke many different languages, wore many different kinds of dress, ate different kinds of food, practised different professions and belonged to different religion and castes. To the problem of unity was added the problem of development. At Independence, the vast majority of Indians lived in the villages. Farmers and peasants depended on the monsoon for their survival. So did the non-farm sector of the rural economy, for if the crops failed, barbers, carpenters, weavers and other service groups would not get paid for their services either. In the cities, factory workers lived in crowded slums with little access to education or health care. Clearly, the new nation had to lift its masses out of poverty by increasing the productivity of agriculture and by promoting new, job-creating industries.

Unity and development had to go hand in hand. If the divisions between different sections of India were not healed, they could result in violent and costly conflicts – high castes fighting with low castes, Hindus with Muslims and soon. At the same time, if the fruits of economic development did not reach the broad masses of the population, it could create fresh divisions – for example, between the rich and the poor, between cities and the countryside, between regions of India that were prosperous and regions that lagged behind.

A Constitution is Written Between December 1946 and November 1949, some three hundred Indians had a series of meetings on the country’s political future. The meetings of this “Constituent Assembly” were held in New Delhi, but the participants came from all over India, and from different political parties. These discussions resulted in the framing of the Indian Constitution, which was adopted on 26 January 1950. One feature of the Constitution was its adoption of universal adult franchise. All Indians above the age of 21 would be al lowed to vote in state and national elections. This was a revolutionary step – for never before had Indians been allowed to choose their own leaders. In other countries, such as the United Kingdom and the United States, this right had been granted in stages.

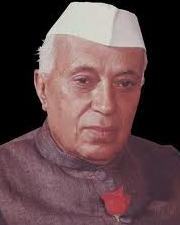

A second feature of the Constitution was that it guaranteed equality before the law to all citizens, regardless of their caste or religious affiliation. There were some Indians who wished that the political system of the new nation be based on Hindu ideals, and that India itself be run as a Hindu state. They pointed to the example of Pakistan, a country created explicitly to protect and further the interests of a particular religious community – the Muslims. However, the Indian Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was of the opinion that India could not and must not become a “Hindu Pakistan”. Besides Muslims, India also had large populations of Sikhs and Christians, as well as many Parsis and Jains. Under the new Constitution, they would have the same rights as Hindus.

A third feature of the Constitution was that it offered special privileges for the poorest and most disadvantaged Indians. The practice of untouchability, described as a “slur and a blot” on the “fair name of India”, was abolished. Hindu temples, previously open to only the higher castes, were thrown open to all. After a long debate, the Constituent Assembly also recommended that a certain percentage of seats in legislatures as well as jobs in government be reserved for members of the lowest castes. One member of the Constituent Assembly, H.J. Khandekar's statement is worth reading : We were suppressed for thousands of years. You engaged us in your service to serve your own ends and suppressed us to such an extent that neither our minds nor our bodies and nor even our hearts work, nor are we able to march forward.

The Constituent Assembly spent many days discussing the powers of the central government versus those of the state governments. The Constitution sought to balance between centre and states power by providing three lists of subjects: a Union List, with subjects such as taxes, defence and foreign affairs, which would be the exclusive responsibility of the Centre; a State List of subjects, such as education and health, which would be taken care of principally by the states; a Concurrent List, under which would come subjects such as forests and agriculture, in which the Centre and the states would have joint responsibility.

Another major debate in the Constituent Assembly concerned language. Many members believed that the English language should leave India with the British rulers. Its place, they argued, should be taken by Hindi. However, those who did not speak Hindi were of a different opinion. Speaking in the Assembly, T.T. Krishnamachari conveyed “a warning on behalf of people of the South”, some of whom threatened to separate from India if Hindi was imposed on them. A compromise was finally arrived at: namely, that while Hindi would be the “official language” of India, English would be used in the courts, the services, and communications between one state and another.

Many Indians contributed to the framing of the Constitution. But perhaps the most important role was played by Dr B.R. Ambedkar, who was Chairman of the Drafting Committee, and under whose supervision the document was finalised. In his final speech to the Constituent Assembly, Dr Ambedkar pointed out that political democracy had to be accompanied by economic and social democracy. Giving the right to vote would not automatically lead to the removal of other inequalities such as between rich and poor, or between upper and lower castes. With the new Constitution, he said, India was going to enter into a life of contradictions. In politics we will have equality and in social and economic life we will have inequality. In politics we will be recognising the principle of one man one vote and one value. In our social and economic life, we shall, by reason of our social and economic structure, continue to deny the principle of one man one value.

Back in the 1920s, the Indian National Congress had promised that once the country won independence, each major linguistic group would have its own province. However, after independence the Congress did not take any steps to honour this promise due to fear of furher divisionism. The Kannada speakers, Malayalam speakers, the Marathi speakers, had all looked forward to having their own state. The strongest protests, however, came from the Telugu-speaking districts of what was the Madras Presidency. When Nehru went to campaign there during the general elections of 1952, he was met with black flags and slogans demanding “We want Andhra”. In October of that year, a veteran Gandhian named Potti Sriramulu went on a hunger fast demanding the formation of Andhra state to protect the interests of Telugu speakers. On 15 December 1952, fifty-eight days into his fast, Potti Sriramulu died. As a newspaper put it, “the news of the passing away of Sriramulu engulfed entire Andhra in chaos”. The protests were so widespread and intense that the central government was forced to give in to the demand.

Thus, on 1 October 1953, the new state of Andhra Pradesh came into being. After the creation of Andhra, other linguistic communities also demanded their own separate states. A States Reorganisation Commission was set up, which submitted its report in 1956, recommending the redrawing of district and provincial boundaries to form compact provinces of Assamese, Bengali, Oriya, Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada and Telugu speakers respectively. The large Hindi -speaking region of north India was broken up into several states.

A little later, in 1960, the bilingual state of Bombay was divided into separate states for Marathi and Gujarati speakers. In 1966, the state of Punjab was also divided into Punjab and Haryana, the former for the Punjabi speakers (who were also mostly Sikhs), the latter for the rest (who spoke not Punjabi but versions of Haryanvi or Hindi).

Planning for Development

Lifting India and Indians out of poverty, and building a modern technical and industrial base were among the major objectives of the new nation. In 1950, the government set up a Planning Commission to help design and execute suitable policies for economic development. There was a broad agreement on what was called a “mixed economy” model. Here, both the State and the private sector would play important and complementary roles in increasing production and generating jobs. What, specifically, these roles were to be – which industries should be initiated by the state and which by the market, how to achieve a balance between the different regions and states – was to be defined by the Planning Commission. In 1956, the Second Five Year Plan was formulated. This focused strongly on the development of heavy industries such as steel, and on the building of large dams.

The search for an independent foreign policy

India gained freedom soon after the devastations of the Second World War. At that time a new international body – the United Nations – formed in 1945 was in its infancy. The 1950s and 1960s saw the emergence of the Cold War, that is, power rivalries and ideological conflicts between the USA and the USSR, with both countries creating military alliances. This was also the period when colonial empires were collapsing and many countries were attaining independence. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who was also the foreign minister of newly independent India, developed free India’s foreign policy in this context. Non-alignment formed the bedrock of this foreign policy.

Led by statesmen from Egypt, Yugoslavia, Indonesia, Ghana and India, the non-aligned movement urged countries not to join either of the two major alliances. But this policy of staying away from alliances was not a matter of remaining “isolated” or “neutral”. The former means remaining aloof from world affairs whereas non-aligned countries such as India played an active role in mediating between the American and Soviet alliances. They tried to prevent war — often taking a humanitarian and moral stand against war. However, for one reason or another, many non-aligned countries including India got involved in wars. By the 1970s, a large number of countries had joined the non-aligned movement.

The Nation, Sixty Four Years On

On 15 August 2011, India celebrated sixty fourth years of its existence as a free nation. Manyforeign observers had felt that India could not survive as a single country, that it would break up into many parts, with each region or linguistic group seeking to form a nation of its own. Others believed that it would come under military rule. However, as many as thirteen general elections have been held since Independence, as well as hundreds of state and local elections. There is a free press, as well as an independent judiciary.

Finally, the fact that people speak different languages or practise different faiths has not come in the way of national unity. On the other hand, deep divisions persist. Despite constitutional guarantees, the Untouchables or, as they are now referred to, the Dalits, face violence and discr imination. And despite the secular ideals enshrined in the Constitution, there have been clashes between different religious groups in many states. Above all, as many observers have noted, the gulf between the rich and the poor has grown over the years. Some parts of India and some groups of Indians have benefited a great deal from economic development. They live in large houses and dine in expensive restaurants, send their children to expensive private schools and take expensive foreign holidays. At the same time many others continue to live below the poverty line. Housed in urban slums, or living in remote villages on lands that yield little, they cannot afford to send their children to school. The Constitution recognises equality before the law, but in real life some Indians are more equal than others. Judged by the standards it set itself at Independence, the Republic of India has not been a great success. But it has not been a failure either.

What happened in Sri Lanka

In 1956, the year the states of India were reorganised on the basis of language, the Parliament of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) introduced an Act recognising Sinhala as the sole official language of the country. This made Sinhala the medium of instruction in all state schools and colleges, in public examinations, and in the courts. The new Act was opposed by the Tamil-speaking minority who lived in the north of the island. For several decades now, a civil war has raged in Sri Lanka, whose roots lie in the imposition of the Sinhala language on the Tamil-speaking minority. And another South Asian country, Pakistan, was divided into two when the Bengali speakers of the east felt that their language was being suppressed. By contrast, India has managed to survive as a single nation, in part because the many regional languages were given freedom to flourish. Had Hindi been imposed on South India, in the way that Urdu was imposed on East Pakistan or Sinhala on northern Sri Lanka, India too might have seen civil war and fragmentation. Contrary to the fears of Jawaharal Nehru and Sardar Patel, linguistic states have not threatened the unity of India. Rather,

they have deepened this unity.

Potti Sriramulu

The Gandhian leader who died fasting for a separate state for Telugu speakers.

Krishna Menon

He led the Indian delegation to the UN between 1952 and 1962 and argued for a policy of non-alignment.

"we have a Muslim minority who are so large in numbers that they cannot, even if they want, go anywhere else. That is a basic fact about which there can be no argument. Whatever the provocation from Pakistan and whatever the indignities and horrors inflicted on non-Muslims there, we have got to deal with this minority in a civilised manner. We must give them security and the rights of citizens in a democratic State." - From, our visionary leader Nehru's letter to the Chief Ministers of states during the days of partition.

0 comments: