In January 1915, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to his homeland after two decades of stay in South Africa, where he went as a lawyer, and in time became a leader of the Indian community in that territory. It was in South Africa that Mahatma Gandhi first forged the distinctive techniques of non-violent protest known as satyagraha, first promoted harmony between religions, and first alerted upper -caste Indians to their discriminatory treatment of low castes and women. The India that Mahatma Gandhi came back to in 1915 was rather different from the one that he had left in 1893. Although still a colony of the British, it was far more active in a political sense. The Indian National Congress now had branches in most major cities and towns. Through the Swadeshi movement of 1905-07 it had greatly broadened its appeal among the middle classes. That movement had thrown up some towering leaders – among them Bal Gangadhar Tilak of Maharashtra, Bipin Chandra Pal of Bengal, and Lala Lajpat Rai of Punjab.

In January 1915, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi returned to his homeland after two decades of stay in South Africa, where he went as a lawyer, and in time became a leader of the Indian community in that territory. It was in South Africa that Mahatma Gandhi first forged the distinctive techniques of non-violent protest known as satyagraha, first promoted harmony between religions, and first alerted upper -caste Indians to their discriminatory treatment of low castes and women. The India that Mahatma Gandhi came back to in 1915 was rather different from the one that he had left in 1893. Although still a colony of the British, it was far more active in a political sense. The Indian National Congress now had branches in most major cities and towns. Through the Swadeshi movement of 1905-07 it had greatly broadened its appeal among the middle classes. That movement had thrown up some towering leaders – among them Bal Gangadhar Tilak of Maharashtra, Bipin Chandra Pal of Bengal, and Lala Lajpat Rai of Punjab.The three were known as “Lal, Bal and Pal”, the alliteration conveying the all-India character of their struggle, since their native provinces were very distant from one another. Where these leaders advocated militant opposition to colonial rule, there was a group of “Moderates” who preferred a more gradual and persuasive approach. Among these Moderates was Gandhiji’s acknowledged political mentor, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, as well as Mohammad Ali Jinnah. On Gokhale’s advice, Gandhiji spent a year travelling around British India, getting to know the land and its peoples.

His first major public appearance was at the opening of the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in February 1916. Among the invitees to this event were the princes and philanthropists whose donations had contributed to the founding of the BHU. Also present were important leaders of the Congress, such as Annie Besant. Compared to these dignitaries, Gandhiji was relatively unknown. He had been invited on account of his work in South Africa, rather than his status within India. When his turn came to speak, Gandhiji charged the Indian elite with a lack of concern for the labouring poor. The opening of the BHU, he said, was “certainly a most gorgeous show”. But he worried about the contrast between the “richly bedecked noblemen” present and “millions of the poor” Indians who were absent. Gandhiji told the privileged invitees that “there is no salvation for India unless you strip yourself of this jewellery and hold it in trust for your countrymen in India”. Gandhiji’s speech at Banaras in February 1916 was, at one level, merely a statement of fact – namely, that Indian nationalism was an elite phenomenon, a creation of lawyers and doctors and landlords. But, at another level, it was also a statement of intent – the first public announcement of Gandhiji’s own desire to make Indian nationalism more properly representative of the Indian people as a whole. In the last month of that year, Gandhiji was presented with an opportunity to put his precepts into practice. At the annual Congress, held in Lucknow in December 1916, he was approached by a peasant from Champaran in Bihar, who told him about the harsh treatment of peasants by British indigo planters.

The Making and Unmaking of Noncooperation

Mahatma Gandhi was to spend much of 1917 in Champaran, seeking to obtain for the peasants security of tenure as well as the freedom to cultivate the crops of their choice. The following year, 1918, Gandhiji was involved in two campaigns in his home state of Gujarat. First, he intervened in a labour dispute in Ahmedabad, demanding better working conditions for the textile mill workers. Then he joined peasants in Kheda in asking the state for the remission of taxes following the failure of their harvest. These initiatives in Champaran, Ahmedabad and Kheda marked Gandhiji out as a nationalist with a deep sympathy for the poor. At the same time, these were all localised struggles.

Then, in 1919, the colonial rulers delivered into Gandhiji’s lap an issue from which he could construct a much wider movement. During the Great War of 1914-18, the British had instituted censorship of the press and permitted detention without trial. Now, on the recommendation of a committee chaired by Sir Sidney Rowlatt, these tough measures were continued. In response, Gandhiji called for a countrywide campaign against the “Rowlatt Act”.

In towns across North and West India, life came to a standstill, as shops shut down and schools closed in response to the bandh call. The protests were particularly intense in the Punjab, where many men had served on the British side in the War – expecting to be rewarded for their service. Instead they were given the Rowlatt Act. Gandhiji was detained while proceeding to the Punjab, even as prominent local Congressmen were arrested. The situation in the province grew progressively more tense, reaching a bloody climax in Amritsar in April 1919, when a British Brigadier ordered his troops to open fire on a nationalist meeting. More than four hundred people were killed in what is known as the Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

It was the Rowlatt satyagraha that made Gandhiji a truly national leader. Emboldened by its success, Gandhiji called for a campaign of “non-cooperation” with British rule. Indians who wished colonialism to end were asked to stop attending schools, colleges and law courts, and not pay taxes. In sum, they were asked to adhere to a “renunciation of (all) voluntary association with the (British) Government”. If noncooperation was effectively carried out, said Gandhiji, India would win swaraj within a year. To further broaden the struggle he had joined hands with the Khilafat Movement that sought to restore the Caliphate, a symbol of Pan-Islamism which had recently been abolished by the Turkish ruler.

Gandhiji hoped that by coupling non-cooperation with Khilafat, India’s two major religious communities, Hindus and Muslims, could collectively bring an end to colonial rule. These movements certainly unleashed a surge of popular action that was altogether unprecedented in colonial India. Students stopped going to schools and colleges run by the government. Lawyers refused to attend court. The working class went on strike in many towns and cities: according to official figures, there were 396 strikes in 1921, involving 600,000 workers and a loss of seven million workdays. The countryside was seething with discontent too. Hill tribes in northern Andhra violated the forest laws. Farmers in Awadh did not pay taxes. Peasants in Kumaun refused to carry loads for colonial officials.

These protest movements were sometimes carried out in defiance of the local nationalist leadership. Peasants, workers, and others interpreted and acted upon the call to “non-cooperate” with colonial rule in ways that best suited their interests, rather than conform to the dictates laid down from above. “Non-cooperation,” wrote Mahatma Gandhi’s American biographer Louis Fischer, “became the name of an epoch in the life of India and of Gandhiji. Non-cooperation was negative enough to be peaceful but positive enough to be effective. It entailed denial, renunciation, and self-discipline.

What was the Khilafat Movement?

The Khilafat Movement, (1919-1920) was a movement of Indian Muslims, led by Muhammad Ali and Shaukat Ali, that demanded the following: The Turkish Sultan or Khalifa must retain control over the Muslim sacred places in the erstwhile Ottoman empire; the jazirat-ul-Arab (Arabia, Syria, Iraq, Palestine) must remain under Muslim sovereignty; and the Khalifa must be left with sufficient territory to enable him to defend the Islamic faith. The Congress supported the movement and Mahatma Gandhi sought to conjoin it to the Non-cooperation Movement.

As a consequence of the Non-Cooperation Movement the British Raj was shaken to its foundations for the first time since the Revolt of 1857. Then, in February 1922, a group of peasants attacked and torched a police station in the hamlet of Chauri Chaura, in the United Provinces (now, Uttar Pradesh and Uttaranchal).

During the Non-Cooperation Movement thousands of Indians were put in jail. Gandhiji himself was arrested in March 1922, and charged with sedition. Since Gandhiji had violated the law it was obligatory for the Bench to sentence him to six years’ imprisonment, but, said Judge C N Broomfield, “If the course of events in India should make it possible for the Government to reduce the period and release you, no one will be better pleased than I”.

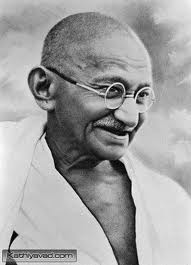

By 1922, Gandhiji had transformed Indian nationalism, thereby redeeming the promise he made in his BHU speech of February 1916. It was no longer a movement of professionals and intellectuals; now, hundreds of thousands of peasants, workers and artisans also participated in it. Many of them venerated Gandhiji, referring to him as their “Mahatma”. They appreciated the fact that he dressed like them, lived like them, and spoke their language. Unlike other leaders he did not stand apart from the common folk, but empathised and even identified with them. This identification was strikingly reflected in his dress: while other nationalist leaders dressed formally, wearing a Western suit or an Indian bandgala, Gandhiji went among the people in a simple dhoti or loincloth. Meanwhile, he spent part of each day working on the charkha (spinning wheel), and encouraged other nationalists to do likewise.

Mahatma Gandhi with the charkha has become the most abiding image of Indian nationalism. In 1921, during a tour of South India, Gandhiji shaved his head and began wearing a loincloth in order to identify with the poor. His new appearance also came to symbolise asceticism and abstinence – qualities he celebrated in opposition to the consumerist culture of the modern world.

Between 1917 and 1922, a group of highly talented Indians attached themselves to Gandhiji. They included Mahadev Desai, Vallabh Bhai Patel, J.B. Kripalani, Subhas Chandra Bose, Abul Kalam Azad, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu, Govind Ballabh Pant and C. Rajagopalachari. Notably, these close associates of Gandhiji came from different regions as well as different religious traditions. In turn, they inspired countless other Indians to join the Congress and work for it. Mahatma Gandhi was released from prison in February 1924, and now chose to devote his attention to the promotion of home-spun cloth (khadi ), and the abolition of untouchability.

For several years after the Non-cooperation Movement ended, Mahatma Gandhi focused on his social reform work. In 1928, however, he began to think of re-entering politics. That year there was an all-India campaign in opposition to the all-White Simon Commission, sent from England to enquire into conditions in the colony. Gandhiji did not himself participate in this movement, although he gave it his blessings, as he also did to a peasant satyagraha in Bardoli in the same year. In the end of December 1929, the Congress held its annual session in the city of Lahore.

The meeting was significant for two things: the election of Jawaharlal Nehru as President, signifying the passing of the baton of leadership to the younger generation; and the proclamation of commitment to “Purna Swaraj”, or complete independence. Now the pace of politics picked up once more. On 26 January 1930, “Independence Day” was observed, with the national flag being hoisted in different venues, and patriotic songs being sung.

Soon after the observance of this “Independence Day”, Mahatma Gandhi announced that he would lead a march to break one of the most widely disliked laws in British India, which gave the state a monopoly in the manufacture and sale of salt. His picking on the salt monopoly was another illustration of Gandhiji’s tactical wisdom. For in every Indian household, salt was indispensable; yet people were forbidden from making salt even for domestic use, compelling them to buy it from shops at a high price. The state monopoly over salt was deeply unpopular; by making it his target, Gandhiji hoped to mobilise a wider discontent against British rule.

The Salt March was notable for at least three reasons. First, it was this event that first brought Mahatma Gandhi to world attention. The march was widely covered by the European and American press. Second, it was the first nationalist activity in which women participated in large numbers. The socialist activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay had persuaded Gandhiji not to restrict the protests to men alone. Kamaladevi was herself one of numerous women who courted arrest by breaking the salt or liquor laws. Third, and perhaps most significant, it was the Salt March which forced upon the British the realisation that their Raj would not last forever, and that they would have to devolve some power to the Indians. To that end, the British government convened a series of “Round Table Conferences” in London. The first meeting was held in November 1930, but without the pre-eminent political leader in India, thus rendering it an exercise in futility.

Gandhiji was released from jail in January 1931 and the following month had several long meetings with the Viceroy. These culminated in what was called the “Gandhi-Irwin Pact’, by the terms of which civil disobedience would be called off, all prisoners released, and salt manufacture allowed along the coast. The pact was criticised by radical nationalists, for Gandhiji was unable to obtain from the Viceroy a commitment to political independence for Indians; he could obtain merely an assurance of talks towards that possible end.

A second Round Table Conference was held in London in the latter part of 1931. Here, Gandhiji represented the Congress. However, his claims that his party represented all of India came under challenge from other parties: from the Muslim League, which claimed to stand for the interests of the Muslim minority; from the Princes, who claimed that the Congress had no stake in their territories;

In 1935, however, a new Government of India Act promised some form of representative government. Two years later, in an election held on the basis of a restricted franchise, the Congress won a comprehensive victory. Now eight out of 11 provinces had a Congress “Prime Minister”, working under the supervision of a British Governor.

At the Second Round Table Conference, London, November 1931 Mahatma Gandhi opposed the demand for separate electorates for “lower castes”. He believed that this would prevent their integration into mainstream society and permanently segregate them from other caste Hindus.

In March 1940, the Muslim League passed a resolution demanding a measure of autonomy for the Muslim-majority areas of the subcontinent. The political landscape was now becoming complicated: it was no longer Indians versus the British; rather, it had become a threeway struggle between the Congress, the Muslim League, and the British. At this time Britain had an all-party government, whose Labour members were sympathetic to Indian aspirations, but whose Conservative Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, was a diehard imperialist who insisted that he had not been appointed the King’s First Minister in order to preside over the liquidation of the British Empire. In the spring of 1942, Churchill was persuaded to send one of his ministers, Sir Stafford Cripps, to India to try and forge a compromise with Gandhiji and the Congress. Talks broke down, however, after the Congress insisted that if it was to help the British defend India from the Axis powers, then the Viceroy had first to appoint an Indian as the Defence Member

In September 1939, two years after the Congress ministries assumed office, the Second World War broke out. Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru had both been strongly critical of Hitler and the Nazis. Accordingly, they promised Congress support to the war effort if the British, in return, promised to grant India independence once hostilities ended.

Quit India

After the failure of the Cripps Mission, Mahatma Gandhi decided to launch his third major movement against British rule. This was the “Quit India” campaign, which began in August 1942. Although Gandhiji was jailed at once, younger activists organised strikes and acts of sabotage all over the country. Particularly active in the underground resistance were socialist members of the Congress, such as Jayaprakash Narayan.

In several districts, such as Satara in the west and Medinipur in the east, “independent” governments were proclaimed. The British responded with much force, yet it took more than a year to suppress the rebellion. “Quit India” was genuinely a mass movement, bringing into its ambit hundreds of thousands of ordinary Indians. It especially energised the young who, in very large numbers, left their colleges to go to jail. However, while the Congress leaders languished in jail, Jinnah and his colleagues in the Satara, 1943 .

Prati Sarkar

During the independence struggle,a type of Parallel Government known as Prati Sarkar came into existence.The people of Satara,under the leadership of Krantisinha Nana Patil,ousted the British officials and took power into their hands. During Quit India Movementof 1942, this parallel government replaced British government for 4.5 years from August 1943 to May 1946. Similar ousters of British power in other areas,led to the formation of similar Parallel Governments in Midnapore in West Bengal and Purnia in Uttar Pradesh. Such was the efficiency and power of these Parallel Governments that for nearly 4.5 years, the British did not even try to capture these areas, fearing defeat;which shows the popular nature of these governments.

Muslim League worked patiently at expanding their influence. It was in these years that the League began to make a mark in the Punjab and Sind, provinces where it had previously had scarcely any presence. In June 1944, with the end of the war in sight, Gandhiji was released from prison. Later that year he held a series of meetings with Jinnah, seeking to bridge the gap between the Congress and the League. In 1945, a Labour government came to power in Britain and committed itself to granting independence to India. Meanwhile, back in India, the Viceroy, Lord Wavell, brought the Congress and the League together for a series of talks. Early in 1946 fresh elections were held to the provincial legislatures. The Congress swept the “General” category, but in the seats specifically reserved for Muslims the League won an overwhelming majority. The political polarisation was complete.

A Cabinet Mission sent in the summer of 1946 failed to get the Congress and the League to agree on a federal system that would keep India together while allowing the provinces a degree of autonomy. After the talks broke down, Jinnah called for a “Direct Action Day” to press the League’s demand for Pakistan. On the designated day, 16 August 1946, bloody riots broke out in Calcutta. The violence spread to rural Bengal, then to Bihar, and then across the country to the United Provinces and the Punjab. In some places, Muslims were the main sufferers, in other places, Hindus. In February 1947, Wavell was replaced as Viceroy by Lord Mountbatten. Mountbatten called onelast round of talks, but when these too proved inconclusive he announced that British India would be freed, but also divided. The formal transfer of power was fixed for 15 August. When that day came, it was celebrated with gusto in different parts of India.

In Delhi, there was “prolonged applause” when the President of the Constituent Assembly began the meeting by invoking the Father of the Nation – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. Outside the Assembly, the crowds shouted “Mahatma Gandhi ki jai”.

The Last Heroic Days

As it happened, Mahatma Gandhi was not present at the festivities in the capital on 15 August 1947. He was in Calcutta, but he did not attend any function or hoist a flag there either. Gandhiji marked the day with a 24-hour fast. The freedom he had struggled so long for had come at an unacceptable price, with a nation divided and Hindus and Muslims at each other’s throats. Through September and October, writes his biographer D.G. Tendulkar, Gandhiji “went round hospitals and refugee camps giving consolation to distressed people”. He “appealed to the Sikhs, the Hindus and the Muslims to forget the past and not to dwell on their sufferings but to extend the right hand of fellowship to each other, and to determine to live in peace ...”

At the initiative of Gandhiji and Nehru, the Congress now passed a resolution on “the rights of minorities”. The party had never accepted the “two-nation theory”: forced against its will to accept Partition, it still believed that “India is a land of many religions and many races, and must remain so”. Whatever be the situation in Pakistan, India would be “a democratic secular State where all citizens enjoy full rights and are equally entitled to the protection of the State, irrespective of the religion to which they belong”. The Congress wished to “assure the minorities in India that it will continue to protect, to the best of its ability, their citizen rights against aggression”.

Many scholars have written of the months after Independence as being Gandhiji’s “finest hour”. After working to bring peace to Bengal, Gandhiji now shifted to Delhi, from where he hoped to move on to the riot-torn districts of Punjab. While in the capital, his meetings were disrupted by refugees who objected to readings from the Koran,or shouted slogans asking why he did not speak of the sufferings of those Hindus and Sikhs still living in Pakistan. In fact, as D.G. Tendulkar writes, Gandhiji “was equally concerned with the sufferings of the minority community in Pakistan. He would have liked to be able to go to their succour. But with what face could he now go there, when he could not guarantee full redress to the Muslims in Delhi?”

There was an attempt on Gandhiji’s life on 20 January 1948, but he carried on undaunted. On 26 January, he spoke at his prayer meeting of how that day had been celebrated in the past as Independence Day. Now freedom had come, but its first few months had been deeply disillusioning. However, he trusted that “the worst is over”, that Indians would henceforth work collectively for the “equality of all classes and creeds, never the domination and superiority of the major community over a minor, however insignificant it may be in numbers or influence”.

He also permitted himself the hope “that though geographically and politically India is divided into two, at heart we shall ever be friends and brothers helping and respecting one another and be one for the outside world”. Gandhiji had fought a lifelong battle for a free and united India; and yet, when the country was divided, he urged that the two parts respect and befriend one another. Other Indians were less forgiving. At his daily prayer meeting on the evening of 30 January, Gandhiji was shot dead by a young man. The assassin, who surrendered afterwards, was a Brahmin from Pune named Nathuram Godse, the editor of an extremist Hindu newspaper who had denounced Gandhiji as “an appeaser of Muslims”.

In the 1920s, Jawaharlal Nehru was increasingly influenced by socialism, and he returned from Europe in 1928 deeply impressed with the Soviet Union. As he began working closely with the socialists (Jayaprakash Narayan, Narendra Dev, N.G. Ranga and others), a rift developed between the socialists and the conservatives within the Congress. After becoming the Congress President in 1936, Nehru spoke passionately against fascism, and upheld the demands of workers and peasants. Worried by Nehru’s socialist rhetoric, the conservatives, led by Rajendra Prasad and Sardar Patel, threatened to resign from the Working Committee, and some prominent industrialists in Bombay issued a statement attacking Nehru. Both Prasad and Nehru turned to Mahatma Gandhi and met him at his ashram at Wardha. The latter acted as the mediator, as he often did, restraining Nehru’s radicalism and persuading Prasad and others to see the significance of Nehru’s leadership.

Timeline

1915 Mahatma Gandhi returns from South Africa

1917 Champaran movement

1918 Peasant movements in Kheda (Gujarat), and workers’ movement in Ahmedabad

1919 Rowlatt Satyagraha (March-April)

1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre (April)

1921 Non-cooperation and Khilafat Movements

1928 Peasant movement in Bardoli

1929 “Purna Swaraj” accepted as Congress goal at the Lahore Congress (December)

1930 Civil Disobedience Movement begins; Dandi March (March-April)

1931 Gandhi-Irwin Pact (March); Second Round Table Conference (December)

1935 Government of India Act promises some form of representative government

1939 Congress ministries resign

1942 Quit India Movement begins (August)

1946 Mahatma Gandhi visits Noakhali and other riot-torn areas to stop communal violence

Add to your vocabulary

Seething : (adv) in a state of extreme agitation, esp through anger. Eg :The nation seethed with suppressed revolutionary activity seething movement.

In defiance of : In spite of; contrary to: went on strike in defiance of union policy.

Formidable : Difficult to undertake: a formidable challenge; a formidable opponent.

Indictment :

clumsily : Lacking physical coordination, skill, or grace; awkward. Eg : whenever they have spoken they have done it clumsily and you have felt irritated.

Dreaded : To be very afraid. Eg : I tell you they have dreaded you, because of your irritability and impatience with them.

Bedecked : To adorn. Eg : He worried about the contrast between the “richly bedecked noblemen” and “millions of the poor” Indians.

Venerate : To regard with respect. Eg : Many of them venerated Gandhiji, referring to him as their “Mahatma”.

Asceticism : The principles and practices of an ascetic; extreme self-denial and austerity.

Abstinence : The act or practice of refraining from indulging an appetite or desire.

Source : THEMES IN INDIAN HISTORY – PART III -Chapter 4.

As it happened, Mahatma Gandhi was not present at the festivities in the capital on 15 August 1947. He was in Calcutta, but he did not attend any function or hoist a flag there either. Gandhiji marked the day with a 24-hour fast. The freedom he had struggled so long for had come at an unacceptable price, with a nation divided and Hindus and Muslims at each other’s throats. Through September and October, writes his biographer D.G. Tendulkar, Gandhiji “went round hospitals and refugee camps giving consolation to distressed people”. He “appealed to the Sikhs, the Hindus and the Muslims to forget the past and not to dwell on their sufferings but to extend the right hand of fellowship to each other, and to determine to live in peace ...”

At the initiative of Gandhiji and Nehru, the Congress now passed a resolution on “the rights of minorities”. The party had never accepted the “two-nation theory”: forced against its will to accept Partition, it still believed that “India is a land of many religions and many races, and must remain so”. Whatever be the situation in Pakistan, India would be “a democratic secular State where all citizens enjoy full rights and are equally entitled to the protection of the State, irrespective of the religion to which they belong”. The Congress wished to “assure the minorities in India that it will continue to protect, to the best of its ability, their citizen rights against aggression”.

Many scholars have written of the months after Independence as being Gandhiji’s “finest hour”. After working to bring peace to Bengal, Gandhiji now shifted to Delhi, from where he hoped to move on to the riot-torn districts of Punjab. While in the capital, his meetings were disrupted by refugees who objected to readings from the Koran,or shouted slogans asking why he did not speak of the sufferings of those Hindus and Sikhs still living in Pakistan. In fact, as D.G. Tendulkar writes, Gandhiji “was equally concerned with the sufferings of the minority community in Pakistan. He would have liked to be able to go to their succour. But with what face could he now go there, when he could not guarantee full redress to the Muslims in Delhi?”

There was an attempt on Gandhiji’s life on 20 January 1948, but he carried on undaunted. On 26 January, he spoke at his prayer meeting of how that day had been celebrated in the past as Independence Day. Now freedom had come, but its first few months had been deeply disillusioning. However, he trusted that “the worst is over”, that Indians would henceforth work collectively for the “equality of all classes and creeds, never the domination and superiority of the major community over a minor, however insignificant it may be in numbers or influence”.

He also permitted himself the hope “that though geographically and politically India is divided into two, at heart we shall ever be friends and brothers helping and respecting one another and be one for the outside world”. Gandhiji had fought a lifelong battle for a free and united India; and yet, when the country was divided, he urged that the two parts respect and befriend one another. Other Indians were less forgiving. At his daily prayer meeting on the evening of 30 January, Gandhiji was shot dead by a young man. The assassin, who surrendered afterwards, was a Brahmin from Pune named Nathuram Godse, the editor of an extremist Hindu newspaper who had denounced Gandhiji as “an appeaser of Muslims”.

In the 1920s, Jawaharlal Nehru was increasingly influenced by socialism, and he returned from Europe in 1928 deeply impressed with the Soviet Union. As he began working closely with the socialists (Jayaprakash Narayan, Narendra Dev, N.G. Ranga and others), a rift developed between the socialists and the conservatives within the Congress. After becoming the Congress President in 1936, Nehru spoke passionately against fascism, and upheld the demands of workers and peasants. Worried by Nehru’s socialist rhetoric, the conservatives, led by Rajendra Prasad and Sardar Patel, threatened to resign from the Working Committee, and some prominent industrialists in Bombay issued a statement attacking Nehru. Both Prasad and Nehru turned to Mahatma Gandhi and met him at his ashram at Wardha. The latter acted as the mediator, as he often did, restraining Nehru’s radicalism and persuading Prasad and others to see the significance of Nehru’s leadership.

Timeline

1915 Mahatma Gandhi returns from South Africa

1917 Champaran movement

1918 Peasant movements in Kheda (Gujarat), and workers’ movement in Ahmedabad

1919 Rowlatt Satyagraha (March-April)

1919 Jallianwala Bagh massacre (April)

1921 Non-cooperation and Khilafat Movements

1928 Peasant movement in Bardoli

1929 “Purna Swaraj” accepted as Congress goal at the Lahore Congress (December)

1930 Civil Disobedience Movement begins; Dandi March (March-April)

1931 Gandhi-Irwin Pact (March); Second Round Table Conference (December)

1935 Government of India Act promises some form of representative government

1939 Congress ministries resign

1942 Quit India Movement begins (August)

1946 Mahatma Gandhi visits Noakhali and other riot-torn areas to stop communal violence

Add to your vocabulary

Seething : (adv) in a state of extreme agitation, esp through anger. Eg :The nation seethed with suppressed revolutionary activity seething movement.

In defiance of : In spite of; contrary to: went on strike in defiance of union policy.

Formidable : Difficult to undertake: a formidable challenge; a formidable opponent.

Indictment :

clumsily : Lacking physical coordination, skill, or grace; awkward. Eg : whenever they have spoken they have done it clumsily and you have felt irritated.

Dreaded : To be very afraid. Eg : I tell you they have dreaded you, because of your irritability and impatience with them.

Bedecked : To adorn. Eg : He worried about the contrast between the “richly bedecked noblemen” and “millions of the poor” Indians.

Venerate : To regard with respect. Eg : Many of them venerated Gandhiji, referring to him as their “Mahatma”.

Asceticism : The principles and practices of an ascetic; extreme self-denial and austerity.

Abstinence : The act or practice of refraining from indulging an appetite or desire.

Source : THEMES IN INDIAN HISTORY – PART III -Chapter 4.

0 comments: